LEST WE FORGET: REMEMBERING CANADIAN WAR ART

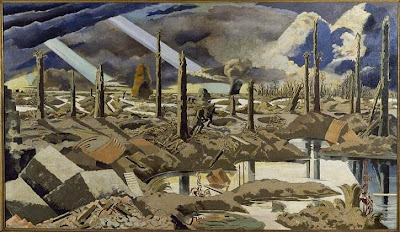

Years ago my post-graduate studies brought me to the Imperial War Museum on an assignment about war artists and the art of World War I. Studying amongst the numerous great galleries and museums of London, you get very used to seeing art first hand instead of just in textbooks. For that particular essay I had scouted out the paintings I wanted to reference in the Imperial War Museum in advance of arriving. When I got there I found what I was looking for, with the exception of a crucial example of a wartime painting that bolstered by essay’s argument. That painting was Paul Nash’s Void, and I had thought that it was located at the museum. I cited the painting from a textbook illustration, and never saw it in person.

Living in Toronto a few years later I took a pilgrimage-like weekend trip to Owen Sound to visit the Tom Thomson Gallery and the little old churchyard where his gravestone resides near where he grew up. At this time, the Tom Thomson Gallery was playing host to a travelling exhibition called Dark Matter: The Great War and Fading Memory. To my great surprise, I walked into the show to find Paul Nash’s Void that had eluded my presence in London. I had in fact been confused regarding the whereabouts of this painting, which was not in fact owned by the Imperial War Museum like so many of Nash’s paintings but rather by our very own National Gallery of Canada. It was in Owen Sound on loan for the exhibition.

(Paul Nash Void 1918 oil on canvas (National Gallery of Canada))

I was thrilled to see the painting in person but furthermore the whole show acted as a reminder of just how integrated and integral Canadian war artists were amongst the Allied troops during World War One. Paul Nash was a British artist who was associated with the art movement, Vorticism (the very same movement that praises speed, technology and modernity that inspired Sybil Andrews and the Grosvenor School of Printmakers) Like Paul Nash, artists were enlisted as ‘Official’ war artists and were sent with regiments to the frontlines in order to document war efforts. Many of these artists were Canadians, as Canadian involvement in World War One was extensive.

Paul Nash The Menin Road 1919 (another example of Nash's war art))

(CRW Nevinson (British) Road to Ypres 1916 oil on canvas (example of Vorticism and war art))

Umberto Boccioni (Italian) Charge of the Lancers 1915 (example of Italian Futurism and war art))

This blog will showcase Canadian war artists’ work during World War One. These works are interesting to look at because often they deviate from the typical styles and or themes that the artists’ regularly did. The art of World War One is quite distinctive and could almost be considered an art movement of it’s own. Paul Nash’s manner of painting is archetypical of the World War One art. Stylistically compositions tended to be angular, linear and highly suggestive of movement, speed, industry and hardship. These features draw heavily from Vorticism and Italian Futurism, however the war artists were not glorifying war like Futurists and often Vorticists before the onset of the war. On the contrary, Paul Nash is noted to have remarked, “I am no longer an artist, I am a messenger to those who want the war to go on forever… and may it burn their lousy souls.”

(J.W. Beatty Ablain St-Nazaire 1918 oil on canvas (Canadian War Museum))

David Milne Ablain St-Nazaire Church from Lorette Ridge Looking toward Souchez and Vimy 1918 (National Gallery of Canada) Beatty and Milne capturing the same subject)

Maurice Cullen Dead Horse and Rider in a Trench 1918 oil on canvas (Canadian War Museum))

David Milne Shell Holes and Wire at the Old German Line on Vimy Ridge (National Gallery of Canada))

Frank Johnston Looking into the Blue 1918 (Canadian War Museum))

Like Nash, official Canadian war artists were disgusted by the horrors of war. The first four Canadian artists appointed by the Canadian War Memorials Fund were William Beatty, Fred Varley, Maurice Cullen, and Charles Simpson. They were given the rank of Captains and had full military pay. Within a short time though however, the Canadian War Memorial Fund instigated by Lord Beaverbrook had as many as 20 artists conscripted with the Canadian troops. David Milne was quite prolific while in service in France, and Frank Johnston was commissioned to paint the home front bases.

Varley wrote to his wife in 1919 about the war:

I’m mighty thankful I’ve left France- I never want to see it again… I’m going to paint a picture of it, but heavens it can’t say a thousandth part of a story… we are forever tainted with its abortiveness and it’s cruel drama- and for the life of me I don’t know how that can help progression. It is foul and smelly and heartbreaking.

On another occasion that year Varley wrote to his friend Arthur Lismer:

I tell you Arthur, your wildest nightmares pale before reality. How the devil one can paint anything to express such is beyond me.

Yet he managed to paint rather successfully.

(Frederick Varley For What? circa 1918 oil on canvas (Canadian War Museum))

(Frederick Varley German Prisoners circa 1919 oil on canvas (Canadian War Museum))

(Frederick Varley Some Day the People will Return 1918 oil on canvas (Canadian War Museum))

A.Y. Jackson was also sent overseas as a wartime artist, as Private A.Y. Jackson. In his autobiography he reminisced:

It is logical that artists should be a part of the organization of total war, whether to provide inspiration, information, or comment on the glory of the stupidity of war… What to paint was a problem for the war artist. There was nothing to serve as a guide… The Impressionist technique I had adopted in painting was now ineffective, for visual impressions were not enough.

This statement helps indicate why most war artists seemed to have strayed from their typical styles/ themes and adopted work based on stylistic principles that were fitting for the depiction of war.

(A.Y. Jackson House of Ypres 1918 oil on canvas (Canadian War Museum))

A.Y. Jackson A Copse, Evening 1918 oil on canvas (Canadian War Museum))

Arthur Lismer also rendered his services to the Canadian War Memorial Fund. By his own suggestion he remained on Canadian soil capturing the war effort at the ports in Halifax. Halifax was a vital arrival and departure point for ships carrying troops, medical support, and supplies back and forth across the Atlantic. And Lismer noted having much to document there.

Arthur Lismer Olympic with Returning Soldiers 1919 oil on canvas (Canadian War Museum))

In Canvas of War A.Y. Jackson’s painting A Copse, Evening is likened to the work of Paul Nash, and it is also noted that Jackson admired Nash’s work greatly. Canvas of War also quotes a 1953 Jackson article whereby he wrote:

I went with Augustus John one night to see a gas attack we made on the German lines. It was like a wonderful display of fireworks, with our clouds of gas and the German flares and rockets of all colours.

Jackson’s connection to the two British artists Paul Nash and Augustus John tell us of the comradery and collaboration that took place between Allied artists from all countries involved.

A.Y. Jackson Gas Attack, Lievin 1918 oil on canvas(Canadian War Museum))

Canadian war art was not limited to the frontlines or the ports, the immense war efforts women put forth working in factories making supplies and provisions was also accounted for by the Canadian War Records. A fine example of this is Mabel May’s Women Making Shells.

Mabel May Women Making Shells 1919 oil on canvas (Canadian War Museum))

Some Canadians produced their masterpieces as artists of war and were praised more for their wartime art than for the art at other intervals in their careers. Their paintings might not be featured prominently in general Canadian art history, but they are featured in publications such as Canvas of War: Painting the Canadian Experience 1914-1945. Two such artists are Cyril Barraud and Eric Kennington.

Cyril Barraud The Stretcher-Bearer Party circa 1918 oil on canvas (Canadian War Museum))

Eric Kennington The Conquerors 1918 oil on canvas (Canadian War Museum))

The majority of these hauntingly effective paintings are owned by the Canadian War Memorial Fund, and thus are kept in public institutions. These works are therefore not very often available on the market and therefore talked about less often. Yet, they are an important part of our history and just like they were intended they remind us ‘Lest we Forget’ of the bravery and sacrifice so many encountered at war. Thus this Remembrance Day let us look at these paintings valiantly rendered from frontline to factory so that we may immortalize the heroes involved and understand the devastation and destruction found at the hands of war.

Canadian war artists were also very involved during World War Two, but a single blog barely adequately covers the art of one world war, let along properly cover two!

BY: JILL TURNER